Known Unto God

The First World War poets – Wilfred Owen in particular – were still very much read when I was at school. And I must have been in my teens when I read Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That. Most moving of all was Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, which I read in my late twenties in an edition brought out at the time of a TV adaptation. Brittain lost both her fiancé and her brother, along with many of their friends. And yet, though I had two grandfathers who served in WWI and one of them had even pulled up his trouser leg to show the marks of shrapnel in his calf, I never thought to ask them about their experiences. Nor did I think to talk to my grandmother, my father’s mother, whose older brother had died at Passchendaele in October 1917. Now of course they have all been dead for decades and because my father died so young, I never had the opportunity to talk to him about his uncle and the effect his death had on my grandmother. He was in any case born nearly a decade after his uncle died.

The First World War poets – Wilfred Owen in particular – were still very much read when I was at school. And I must have been in my teens when I read Robert Graves’s Goodbye to All That. Most moving of all was Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, which I read in my late twenties in an edition brought out at the time of a TV adaptation. Brittain lost both her fiancé and her brother, along with many of their friends. And yet, though I had two grandfathers who served in WWI and one of them had even pulled up his trouser leg to show the marks of shrapnel in his calf, I never thought to ask them about their experiences. Nor did I think to talk to my grandmother, my father’s mother, whose older brother had died at Passchendaele in October 1917. Now of course they have all been dead for decades and because my father died so young, I never had the opportunity to talk to him about his uncle and the effect his death had on my grandmother. He was in any case born nearly a decade after his uncle died.

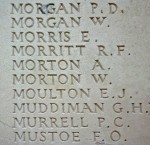

None of my family have ever visited Tyne Cot near Ipres in Belgium where the death of my great uncle, Richard Francis Morritt, is commemorated, I am pretty sure. They were working class people who would not have thought of going abroad. I discovered the exact location from the War Graves Commission web-site and last week on a grey and drizzly October day I stood in front of the his name on the Memorial to the Missing and felt the tears well up. Tyne Cot is the largest British Commonwealth war cemetery in the world. The Memorial to the Missing lists thirty-five thousand men. My great-uncle has no known grave, though he may well be buried in Tyne Cot, for over half the 11, 956 bodies buried there were never identified and their gravestones are simply inscribed with the words ‘Known unto God.’ Or he could be lying somewhere in the fields of Flanders, waiting for some farmer to turn up his bones.

My great-uncle was twenty-six when he died. I felt sad that there was no grave, but glad to have gone and visited him all these years after his death. He is not one of those ‘which have no memorial; who are perished as if they have never been.’ His name will always be there. But oh the thought of those thousands on thousands of young men, and their mothers and fathers, their sisters, wives and sweethearts . . . The context to it all is very well set out in the Memorial Museum in the nearby town of Zonnebeke, though it doesn’t make it any more comprehensible. The scale of the slaughter is staggering.